The terms “decolonization” and “decolonized” are increasingly used across various fields, including Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E). As with many buzzwords, there is a risk of their profound meaning being diluted. But what do these terms mean in the realm of M&E?

The Colonial Legacy in M&E

Colonialism refers to the power structures established during centuries of colonization, where political, economic, and cultural control was imposed by colonizers (Hassnain, 2023). Even after formal colonization ended, these structures remain embedded in global systems. Decolonization, therefore, aims to dismantle these legacies and create equitable systems.

M&E, like other areas of international development and philanthropy, reflects these colonial dynamics with uneven relationships between the Global North and the Global South (Chilisa & Bowman, 2023; Frehiwot, 2019). Funders from the Global North often dictate priorities for projects in the Global South. Terms of Reference (ToR) are written in the Global North and often executed by evaluators from the same region. Methods and tools developed in the Global North are imposed on communities in the Global South, ignoring local contexts and knowledge systems (Frehiwot, 2019; Jordan S. & Hall, 2023; Quantson Davis, 2023).

Within the colonial system, the dominance of Western knowledge, deeply rooted in “academic imperialism,” promotes it as superior while dismissing Indigenous or non-Western knowledge as irrelevant or inferior (Arqaam, n.d.; Jordan S. & Hall, 2023). This has led to an “epistemicide,” the erasure of diverse knowledge systems (Jordan S. & Hall, 2023), and perpetuates methodologies grounded in neutral, rationalist and positivist perspectives (Picciotto, 2023). Conventional M&E assumes the evaluator is an objective and neutral expert while the researched is reduced to a data source, reinforcing unequal relationships and extractive practices (Middernacht et al., 2023; Quantson Davis, 2023). Consequently, M&E often prioritizes funders’ questions over the needs and realities of the populations it serves (Hassnain, 2023; Quantson Davis, 2023; Tolmer, 2024).

Key Questions for the Decolonization of M&E

To move toward decolonized M&E, we must start by asking challenging questions:

- What role, if any, should external evaluators play in decolonized evaluations? (Quantson Davis, 2023)

- Who is considered knowledgeable? Who decides what success looks like? (Vang, 2019)

- “What questions get asked, when, by who, and of whom”?(Jordan S. & Hall, 2023, p. 113)

- Whose truths are being measured, by whom, and how are they being shared? (Hassnain, 2023)

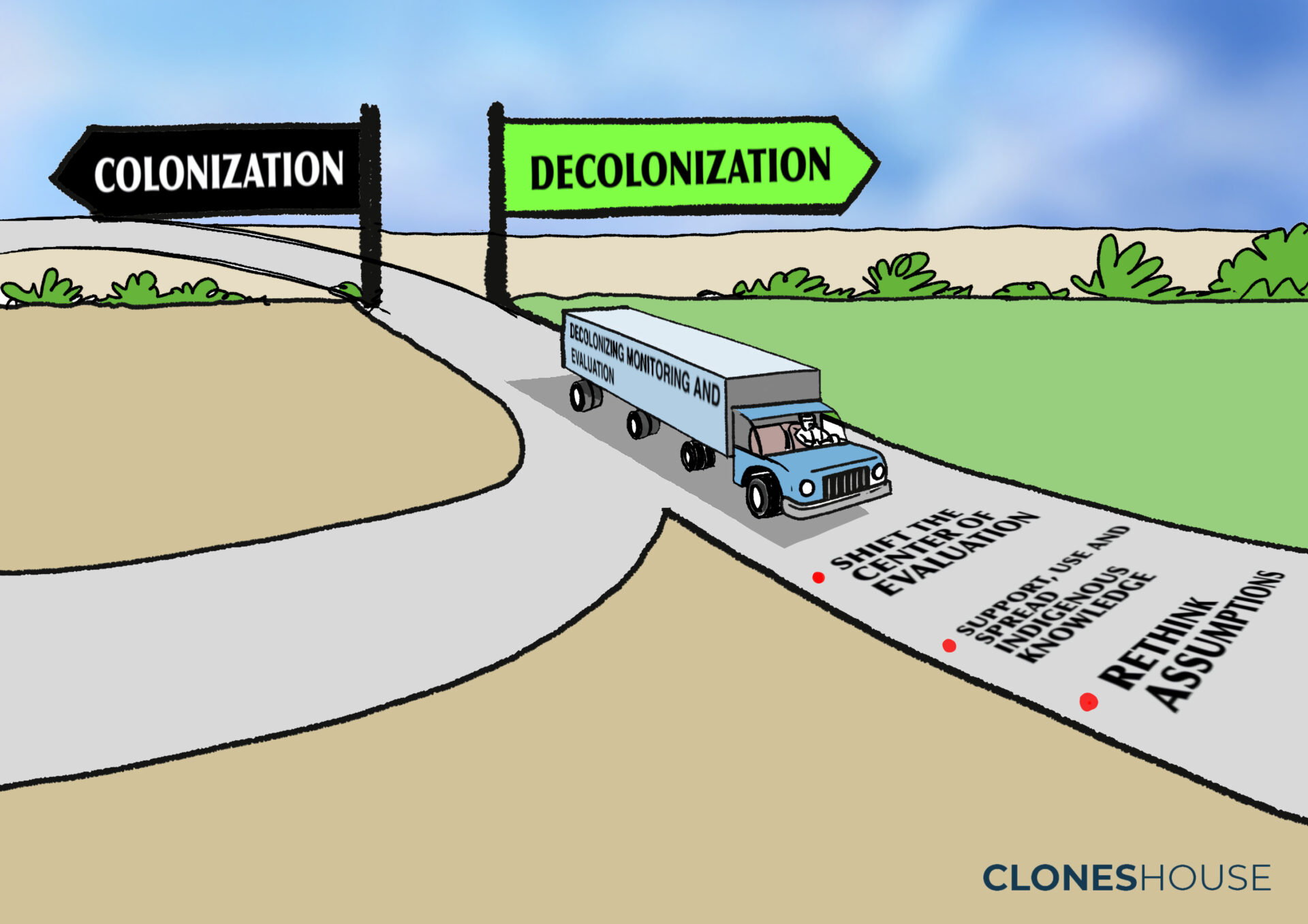

3 Directions to Start Decolonizing M&E

Decolonizing M&E requires context-specific approaches as it should answer “colonial specific issues, geographies and peoples” (Jordan S. & Hall, 2023, p. 113). However, three key areas provide a foundation for change:

1. Shift the Center of Evaluation

The current model often centers funders and external evaluators, reducing local communities to mere providers of information. Decolonized M&E must be framed from the participants’ perspectives and needs (Jordan S. & Hall, 2023; Middernacht et al., 2023). As developed by Quantson Davis (2023), a decolonized evaluation “will place communities and ordinary citizens where they should be: at the center of development work” (p. 228). This involves co-creating evaluation processes with local stakeholders, who should define what is useful in their experience, the relevant questions, and how best to answer them (Arqaam, n.d.; Quantson Davis, 2023; Vang, 2019).

Placing communities and their knowledge at the heart of evaluations shifts power dynamics and ensures that evaluations reflect local realities and needs (Jordan S. & Hall, 2023; Vang, 2019). This approach challenges the extractive nature of traditional M&E, fostering governance models where local actors and knowledge are valued and essential.

Learning from experiences: In Pakistan, an M&E process began by asking the program team what success meant to them, ensuring local realities shaped evaluation goals (Roholt et al., 2023). Similarly, in Jordan, Medair engaged adolescent girls in defining psycho-social well-being, while Caritas India and Action Against Hunger in ZImbabwe co-developed community-defined success metrics (Start Network, 2023). Beyond shaping indicators, communities can also decide how data is collected. In Zimbabwe, HelpAge designed accessible tools, including video-based data collection, to center community voices and knowledge systems (Start Network, 2023). Moreover, instead of defining M&E roles externally, programs can invite communities to determine what responsibilities evaluators should carry when working with them (Roholt et al., 2023).

2. Support, Use and Spread Indigenous Knowledge

Decolonizing M&E requires questioning whose knowledge forms the basis of evaluation (Hassnain, 2023). Western ideologies have long dominated the field, marginalizing local and Indigenous knowledge systems (Jordan S. & Hall, 2023; Quantson Davis, 2023). Recognizing and integrating these systems is essential.

Indigenous frameworks offer culturally relevant perspectives, ensuring evaluations align with local values and contexts (Arqaam, n.d.; Frehiwot, 2019; Hassnain, 2023). Beyond improving relevance, this approach empowers communities, generates local knowledge, and challenges power imbalances (Hassnain, 2023). While Western tools need not be abandoned entirely, they should be critically examined and balanced with Indigenous insights (Arqaam, n.d.).

Learning from experiences: M&E processes must be rooted in local epistemologies. This begins by engaging communities or program participants in defining key concepts and goals, ensuring the evaluation reflects their local knowledge systems (Roholt et al., 2023; Start Network, 2023). Integrating local ways of knowing and doing—such as culturally relevant metaphors like the “river journey” in Indigenous U.S. communities (Eakins et al., 2023) or creating spaces that align with local practices, such as sitting in circles instead of Western classroom settings (Nadeau et al., 2023)—enhances the creation and spread of local knowledge. In Pakistan, the creation of the “Alhamdulillah Tree,” where community members stuck gratitude notes over time, became a data collection tool (Roholt et al., 2023).

3. Rethink Assumptions

The assumption that evaluators are neutral and objective reinforces colonial hierarchies. Evaluators, like everyone else, bring their own biases and worldviews to their work (Hassnain, 2023; Vang, 2019). Acknowledging this, instead of occulting it, is critical to creating evaluations that reflect reality more accurately (Vang, 2019).

Decolonizing M&E also means exploring the concepts of cultural relativism and the pluriverse (Jordan S. & Hall, 2023). It also involves rethinking metrics-driven approaches in favor of social narratives and addressing class and power dynamics between evaluators, institutions, and communities (Hassnain, 2023).

Learning from experiences: As M&E officers, we enter with preconceived ideas of success, progress, failure, and what should be measured—shaped by our academic knowledge and culturally-grounded perspectives. This colonial approach overlooks the fact that communities have the most accurate understanding of their own needs, struggles, and aspirations. Decolonizing M&E requires us to challenge these assumptions and step aside to let local perspectives guide the process. This is exemplified by Akhtar Hameed Khan’s approach in Pakistan, where he immersed himself in local communities, engaging directly with them in everyday spaces, rather than maintaining the distance of the traditional evaluator role (Roholt et al., 2023). Challenging assumptions of neutrality and objectivity allows us to dismantle the hierarchical structures that silence local knowledge and communities.

Challenges and Next Steps

Decolonizing M&E is not easy. It requires time, resources, and a willingness to engage with conflicts that arise from differing perspectives (Vang, 2019). Hassnain (2023) highlights the importance of critically examining power dynamics and redefining notions of progress and success. Despite these difficulties, the potential rewards, including more decolonized, sustainable, and equitable practices, make the effort worthwhile.

For those ready to start this journey, resources and frameworks already exist. Social justice-oriented (Vang, 2019), culturally responsive, decolonial (Jordan S. & Hall, 2023), and Indigenous (Chilisa & Bowman, 2023) frameworks offer practical tools for reimagining evaluation processes. Decolonizing M&E begins with asking hard questions and challenging existing power structures.

Resources:

Arqaam. (n.d.). Why decolonisation matters in M&E – Introducing our new power-critical toolkit. Arqaam Monitoring & Evaluation. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from https://www.arqaam.org/2023/08/29/why-decolonisation-matters-in-me-introducing-our-new-power-critical-toolkit/

Chilisa, B., & Bowman, N. R. (2023). The Why and How of the Decolonization Discourse. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 19(44).

Eakins, D., Gaffney, A., Marum, C., Wangmo, T., Parker, M., & Magarati, M. (2023). Indigenous Evaluation Toolkit: An Actionable Guide for Organizations Serving American Indian/Alaska Native Communities through Opioid Prevention Programming. Seven Directions at the University of Washington. https://www.indigenousphi.org/tribal-opioid-use-disorders-prevention/indigenous-evaluation-toolkit

Frehiwot, M. (2019). Made in Africa Evaluation: Decolonizing Evaluation in Africa. eVALUation Matters, Third Quarter.

Hassnain, H. (2023). Decolonizing Evaluation: Truth, Power, and the Global Evaluation Knowledge Base. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 19(44). https://doi.org/10.56645/jmde.v19i44.803

Jordan S., L., & Hall, J. N. (2023). Framing Anticolonialism in Evaluation: Bridging Decolonizing Methodologies and Culturally Responsive Evaluation. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 19(44).

Middernacht, Z., Narros Lluch, A., & de Iongh, W. (2023). Decolonising monitoring and evaluation: From control to learning [INTRAC]. Decolonising Consultancy. https://www.intrac.org/decolonising-monitoring-and-evaluation-from-control-to-learning/

Nadeau, M., Tibbitts, V., Eagle, R., & Dobervich, G. (2023). Creating and Implementing an Indigenous Evaluation Framework Process With Minnesota Tribes. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 38(1), 35–56. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjpe.75486

Picciotto, R. (2023). Evaluation Transformation Implies Its Decolonization. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 19(44). https://doi.org/10.56645/jmde.v19i44.797

Quantson Davis, R. (2023). Liberated or Recolonized: Making the Case for Embodied Evaluation in Peacebuilding. Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation, 19(44). https://doi.org/10.56645/jmde.v19i44.811

Roholt, R. V., Fink, A., & Ahmed, M. M. (2023). The Learning Partner: Dialogic approaches to monitoring and evaluation in international development. Knowledge Management for Development Journal, 17. https://km4djournal.org/index.php/km4dj/article/view/533

Start Network. (2023). Community-Led Approaches to Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability and Learning (MEAL) Research Grant: Report (p. 13). https://start-network.app.box.com/s/bx0k82csb6ffr6sysu53tr8m22ajs49x

Tolmer, Z. (2024). Decolonizing M&E: What does African monitoring and evaluation look like? Medium – UNDP Strategic Innovation. https://medium.com/@undp.innovation/decolonizing-m-e-what-does-african-monitoring-and-evaluation-look-like-926d97d6f8d1

Vang, K. (2019). Exploring Social Justice-Oriented Evaluations. Congressional Hunger Center. https://hungercenter.org/publications/exploring-social-justice-oriented-evaluations/

About the author:

Binta Souaré is a Fall 2024 intern at Cloneshouse. She holds a Master’s degree in Global Development Policy and is gaining hands-on experience in Monitoring & Evaluation and communication through her internship. Passionate about social justice and equality movements, her work explores policies affecting marginalized communities, as well as the dynamics of decolonization and Global North-South relations. With this blog post, Binta aims to contribute to the ongoing movement to decolonize philanthropy, international development, and M&E.