If we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday, we rob them of tomorrow – John Dewey

Tayo, determined to succeed and make his family proud, fought hard to achieve good grades but still lost woefully. He relentlessly knew he had a unique way of viewing the world, explaining concepts in nature, and creating reflection-provoking arguments from his synthesis of thoughts and ideas. He questioned everything he learned as if a question mark was part of his sentence structure. Sadly, he felt his grades did not properly represent his cognition and wondered if a hidden code to success existed.

Why grades? Why do we need them?

Grades are an integral part of the assessment process as they are an evaluation criterion for students’ progress and achievement in a course/programme. In addition, the results of the obtained data from education tests could be used by instructors and practitioners to decide what modifications should be made in future courses or what points should be emphasized. Sadly, Tayo’s grades always painted a bleak picture no matter how hard he tried. He felt his grades failed to reflect his innate potential and achievement of learning objectives. Little did he know that his crime was his resistance to the “washback effect” all this time.

The washback effect refers to the reciprocal relationship between “academic testing,” “teaching,” and “learner’s behaviour” (Fulcher & Davidson, 2007). In lay terms, this effect explains the influence of tests and examinations on teaching and learning, which implies achievement scores/grades can influence students’ behavior and teachers’ methodology too. The two scenarios below explain this concept better:

- Mallam Adamu teaches his senior secondary school students to prepare them for his tests and their promotional examinations. To ensure they get good grades in WASSCE, he only expects certain responses from them when taking his tests.

- Aisha and Chidinma only focus on specific aspects of learning which they believe will be assessed by their tutor. They know Mrs. Princess loves statistics, and they do not bother themselves with studying non-statistical aspects of their coursework.

As expected, in both scenarios washback effect is seen playing the puppet master as it determines the choices and behaviours of teachers and learners. In either case, this effect excludes students’ ingenuity and hinders the attainment of learning objectives even if those students end up with “good grades.” The washback effect is one of many effects caused by the excessive pursuit of “good grades,” ravaging today’s teaching-learning process. Grades are debatably linked to William Farish in 1792, who only wanted to assess many students quickly; this begs the question, “Are grades still relevant in evaluating the African student today?”

“Education is the most powerful weapon you can use to change the world.” – Nelson Mandela

If education is a weapon, then “contextually relevant content” should be the bullet to be fired through it. Just as accuracy (ability to hit a target) and precision (ability to hit targets repeatedly at the same spot) are important considerations for an effective weapon in armed combat, education would only be effective if it creates the desired change in behaviour and does so consistently.

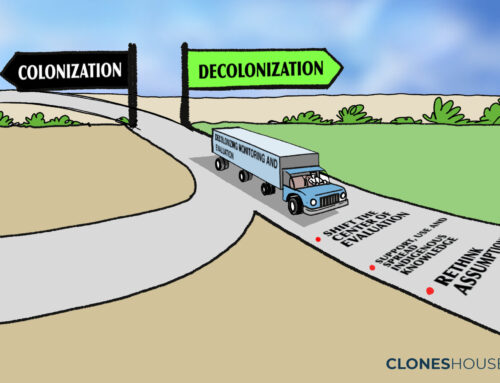

From the angles of accuracy and precision, to ensure education is lethal enough as a weapon, the relevance of the content and the choice of an effective evaluation strategy need to be considered; this is to ensure that the target – the learner is impacted positively concerning the objectives of the education activity. These factors lead to the concept of decolonising education evaluation.

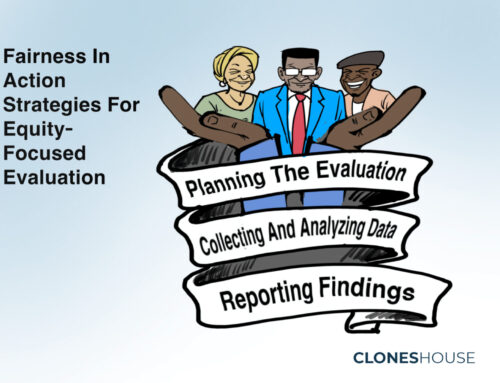

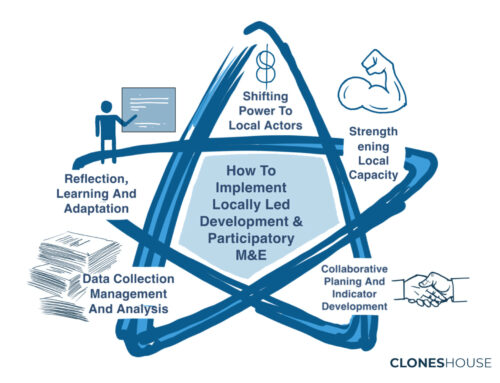

Decolonisation of education evaluation is concerned with the relevance of education assessment. This assessment involves the exposition or translation of the hidden codes, languages, and systems that form the assessment process (Harrison, 2021). In addition, the evaluation aims to identify colonial systems, structures, and relationships and work on challenging those systems (Keele University, 2018) to ensure that education is more objective, realistic, and relevant.

The idea that only one kind of evaluation practice is valid needs to be defunct. Instead, African evaluators must actively construct what is evaluated, when, by whom, and with what methodologies. We must crown our context as king.

“CONTEXT, not CONTENT, is King”

The need to emphasize context in evaluation is to improve the consideration for the inclusivity of non-western terminologies, technology, language, and structure in evaluation practice. In addition, to evaluate educational programmes effectively, one must disrupt cultural imperialism that only emphasizes the Englishman’s culture (Hooks 1994).

Just like in the story of Tayo, who struggled to make good grades, value judgement can be made on education assessments in a way that counters the washback effect but captures more culturally relevant aspects of learned behaviour. This way, African evaluators can see through their own eyes and adequately measure students’ achievement of learning objectives.

Although this implies going against some western approaches and processes that are not contextually relevant, it promotes the inclusion of indigenous frameworks and cultural/historical realities in the evaluation process.

About the Author

Joel Arogunyo is passionate about education evaluation and is currently focused on contributing to education development by bridging the gap in access to quality and functional education as well as data-driven policy advocacy. Joel is adept at quantitative techniques and has a Master’s in Education Measurement and Evaluation. He currently deputises the Regional Manager for sub-Saharan Africa at Cranfield University, United Kingdom, in driving international partnerships and recruitment in Africa.

References

Fulcher, G., & Davidson, F. (2007). Language testing and assessment. Routledge

Harrison, M. (2021). Decolonising assessment: finding the hidden codes. Accessed on 10th September 2022, retrieved from https://juice-journal.com/2021/11/23/decolonising-assessment-finding-the-hidden-codes/

Hooks, b. (1994) Language. In: Hooks, B. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. London and New York: Routledge. pp. 167-176.

Keele University (2019) Manifesto for decolonising the curriculum.

Onyibe, C. O., Uma U. & Ibina, E. (2015). Examination malpractice in Nigeria: Causes and effects on national development. Journal of Education and Practice, 6 (26), pp, 12-18